|

AIR QUALITY MATTERS |

|

City of Westminster |

|

"Recent

changes - neither good for health nor carbon budget?"

|

|

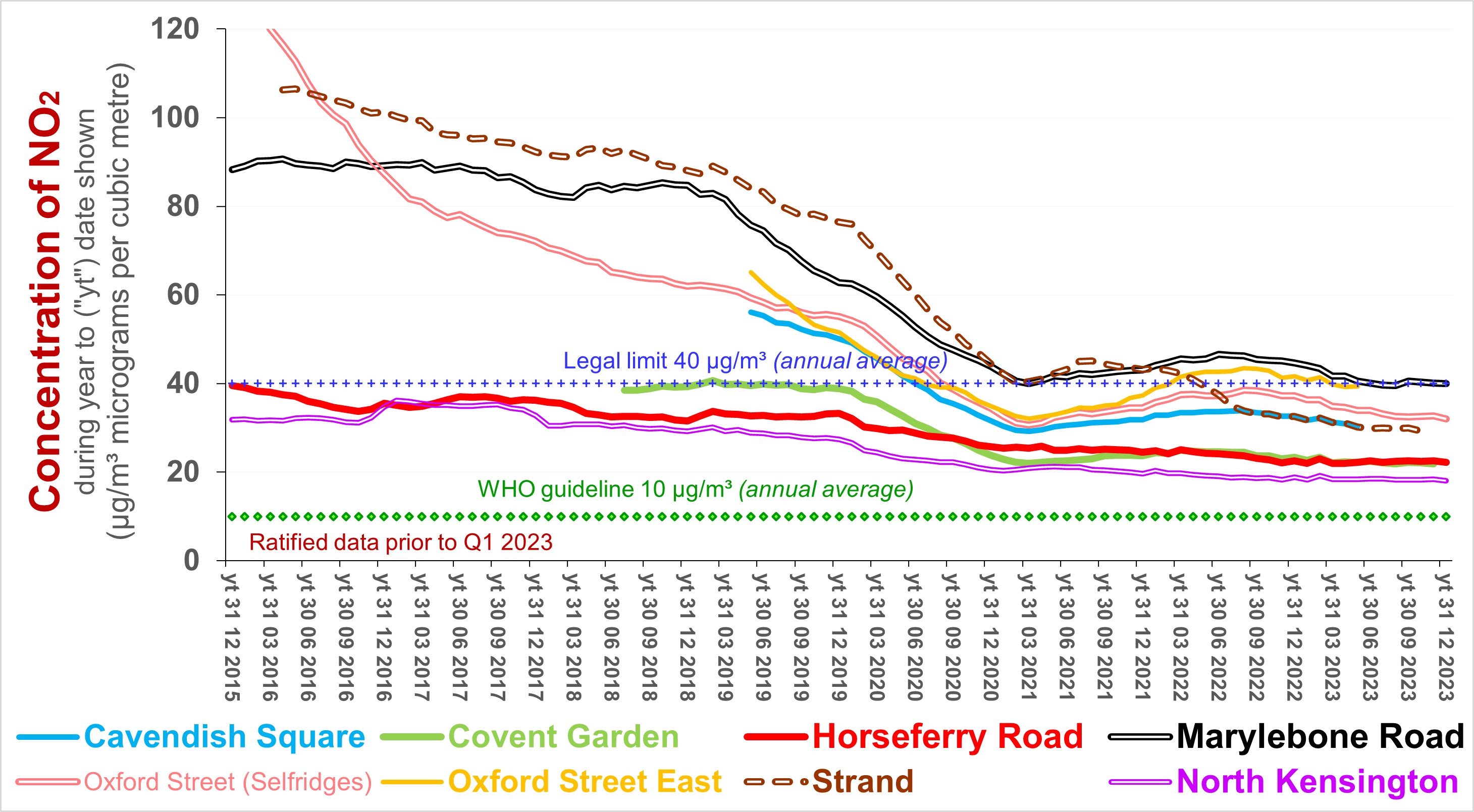

The following chart shows how the

concentration of NO2

(averaged over consecutive periods of 12-months) has changed since 2015 at

some sites in the

City of Westminster where air quality is now being measured

continuously for reference purposes: The steep reduction in NO2 pollution in the vicinity of Selfridges during 2015 and 2016 reflects the success of efforts to revise traffic flows and tighten regulations concerning emissions from buses, taxis and the like. The decrease in concentrations along the Marylebone Road is primarily attributable to the first phase of the ULEZ. Responses to the covid-19 pandemic explain the improvement between March 2020 and early 2021. The subsequent trend suggests that the relaxation of those responses has been matched by vehicle users anticipating the second phase of the ULEZ.

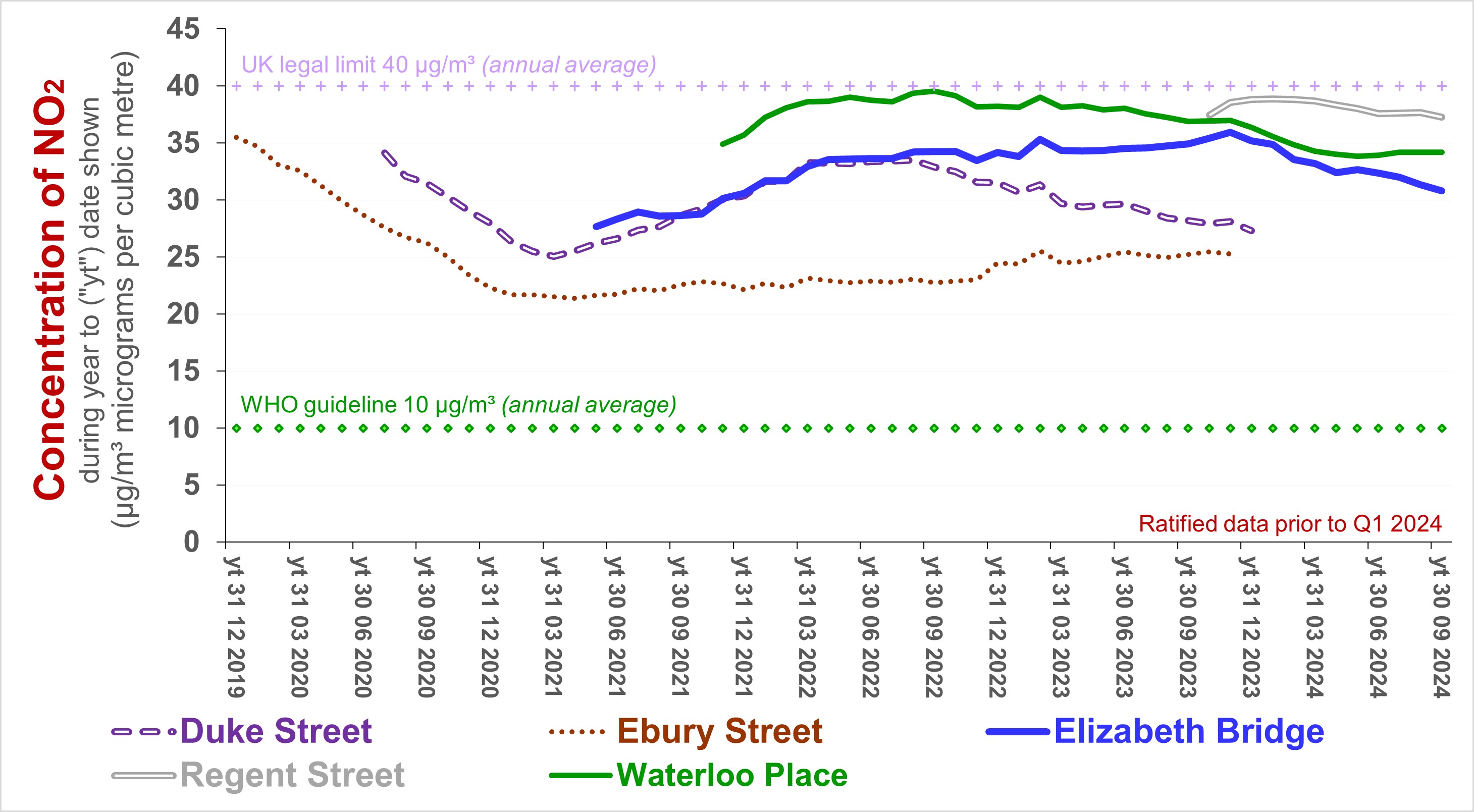

The following chart shows

data similar to the chart above -for other sites in Westminster:

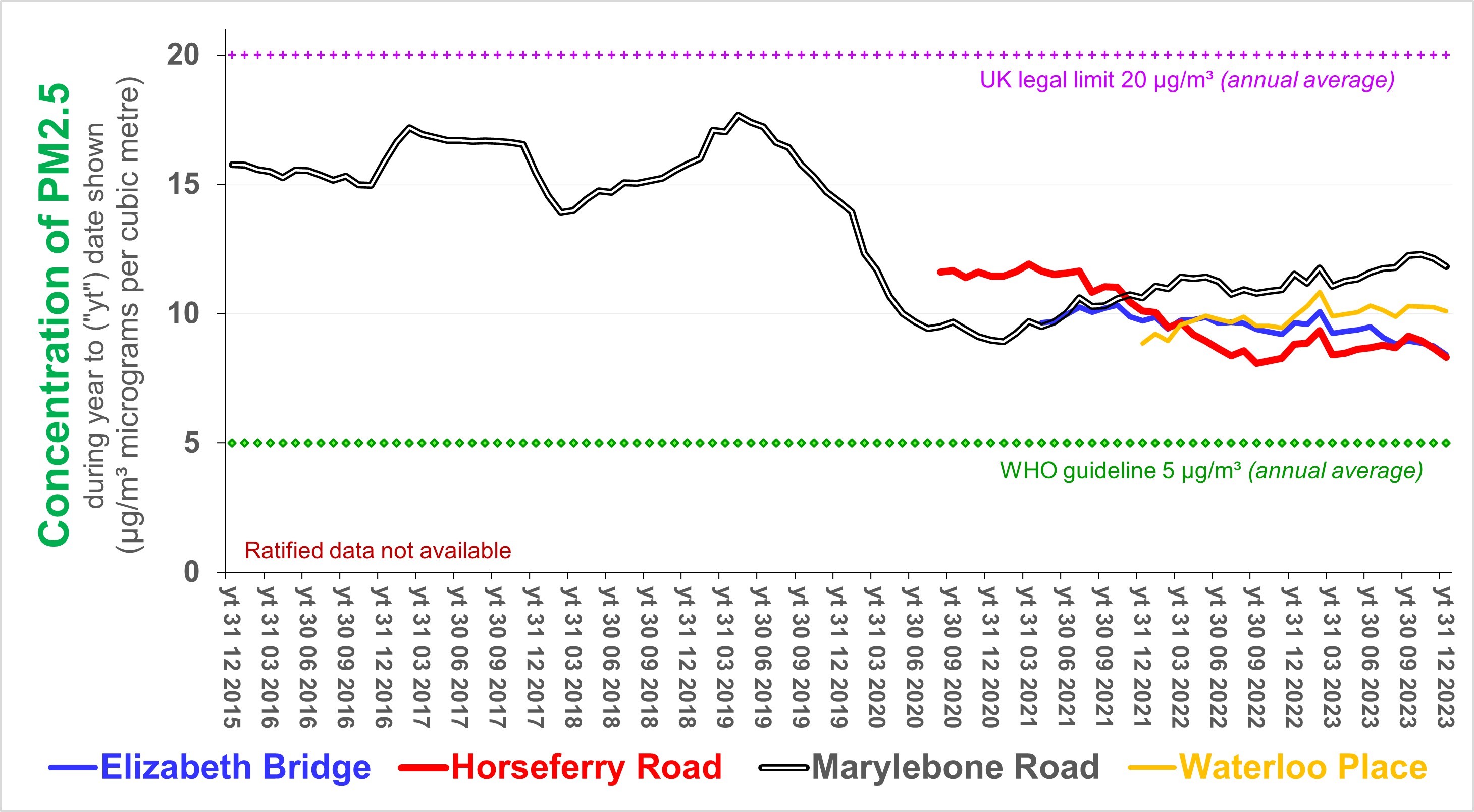

The following chart shows

PM2.5 concentrations measured in Westminster since 2015: The UK government has recently consulted the public about changing the legal limit - to double the World Health Organisation guideine, by 2040. This seems to ignore that, even in London, concentrations are already close to 10 μg/m³ and that that target could be achieved by 2030, especially with the right measures and the allocation of sufficient powers to the GLA.

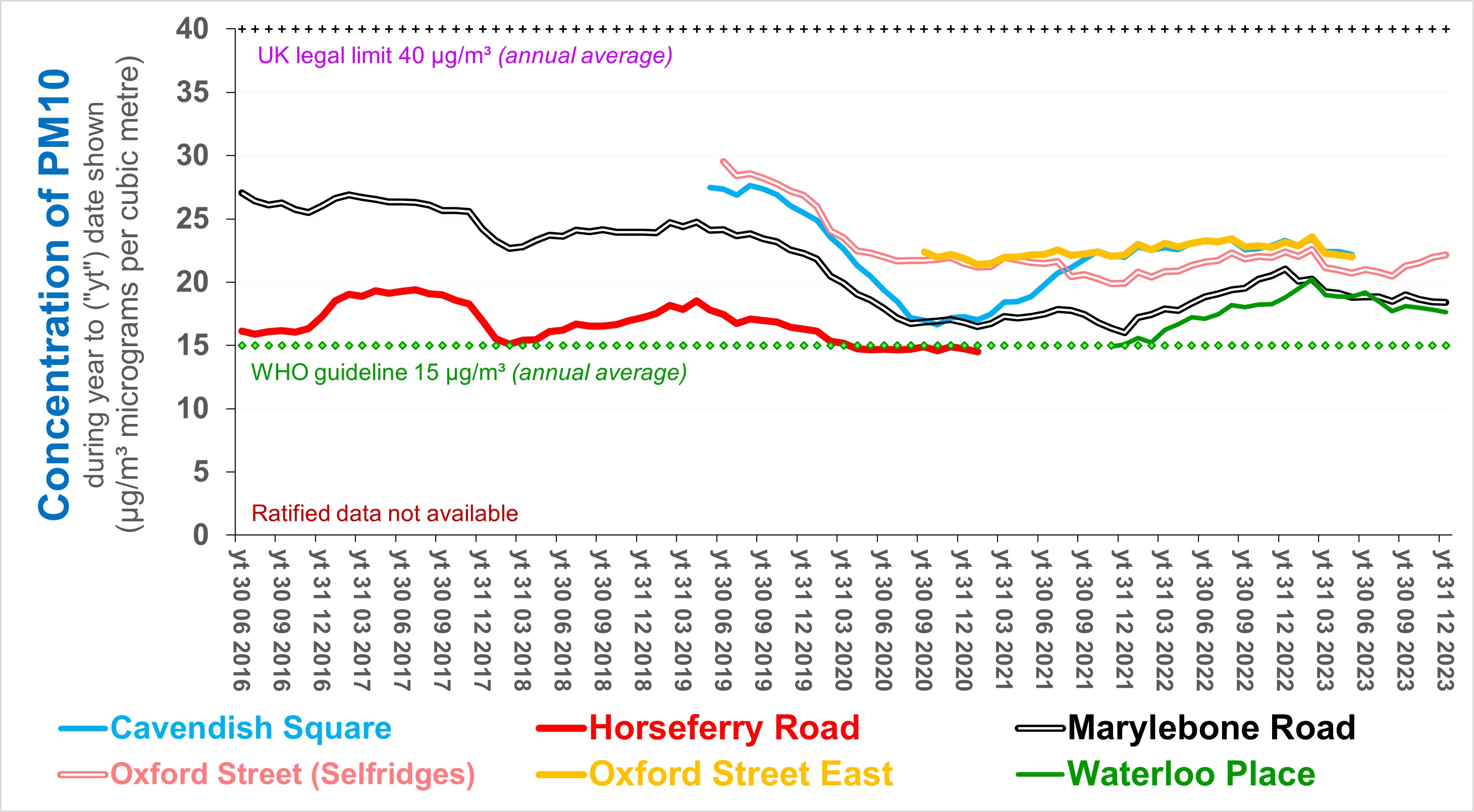

The following chart shows PM10 concentrations measured in Westminster since 2015:

A number of Breathe London sensors are located at sites across Westminster. These set out to monitor both NO2 and PM2.5, but not to reference quality (doing do so when their solar panels supply their batteries with sufficient energy). Click here for charts deriving from Breathe London phase 2

Click here for Westminster City Council NO2 diffusion tube data

Click here for NO2 diffusion tube data measured for HS2

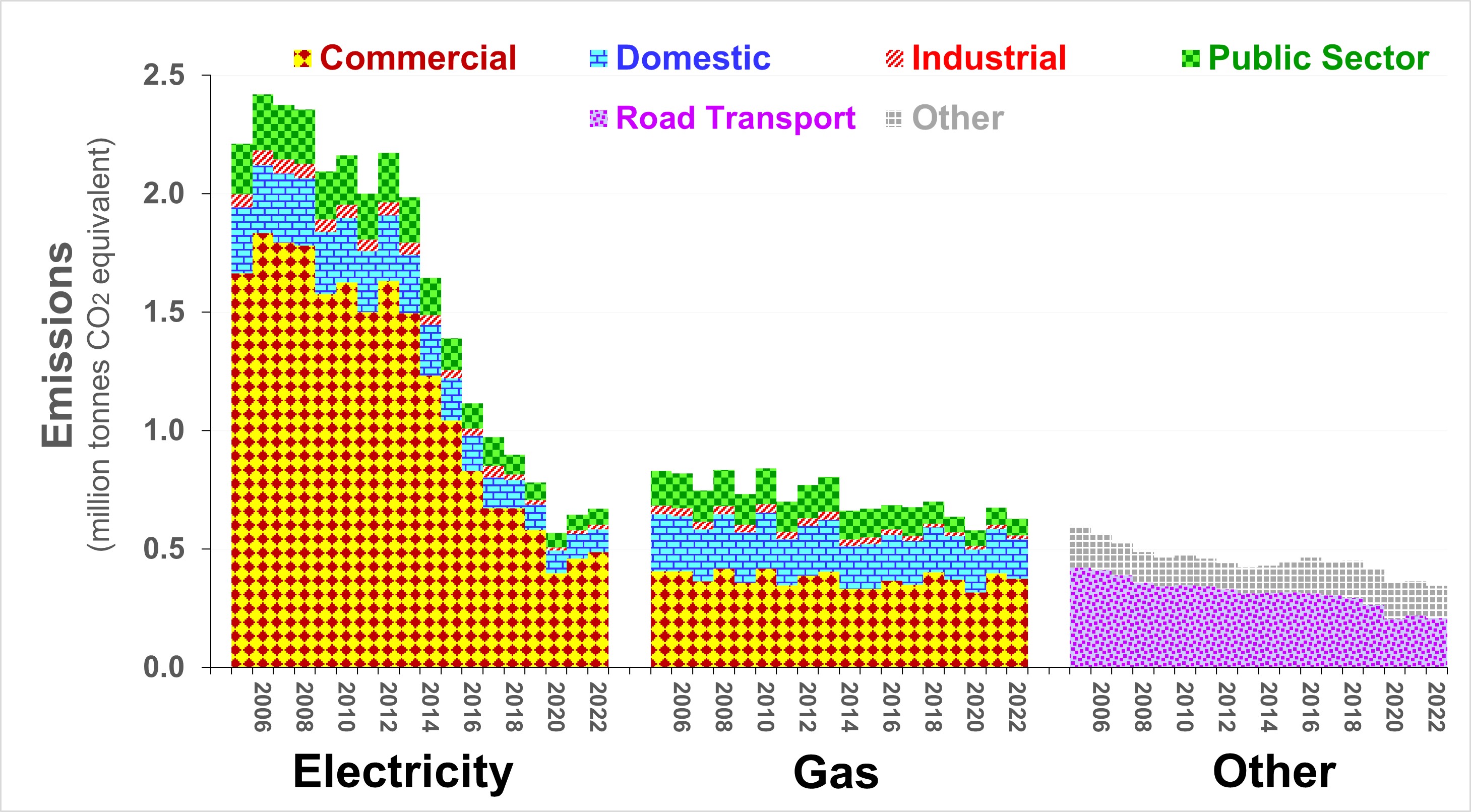

Westminster greenhouse gas emissions Less coal-fired electricity but locking in other carbon-based power; City-wide reduction since 2019: a paltry 10%. Council's estate: c.2% of city-wide emissions.

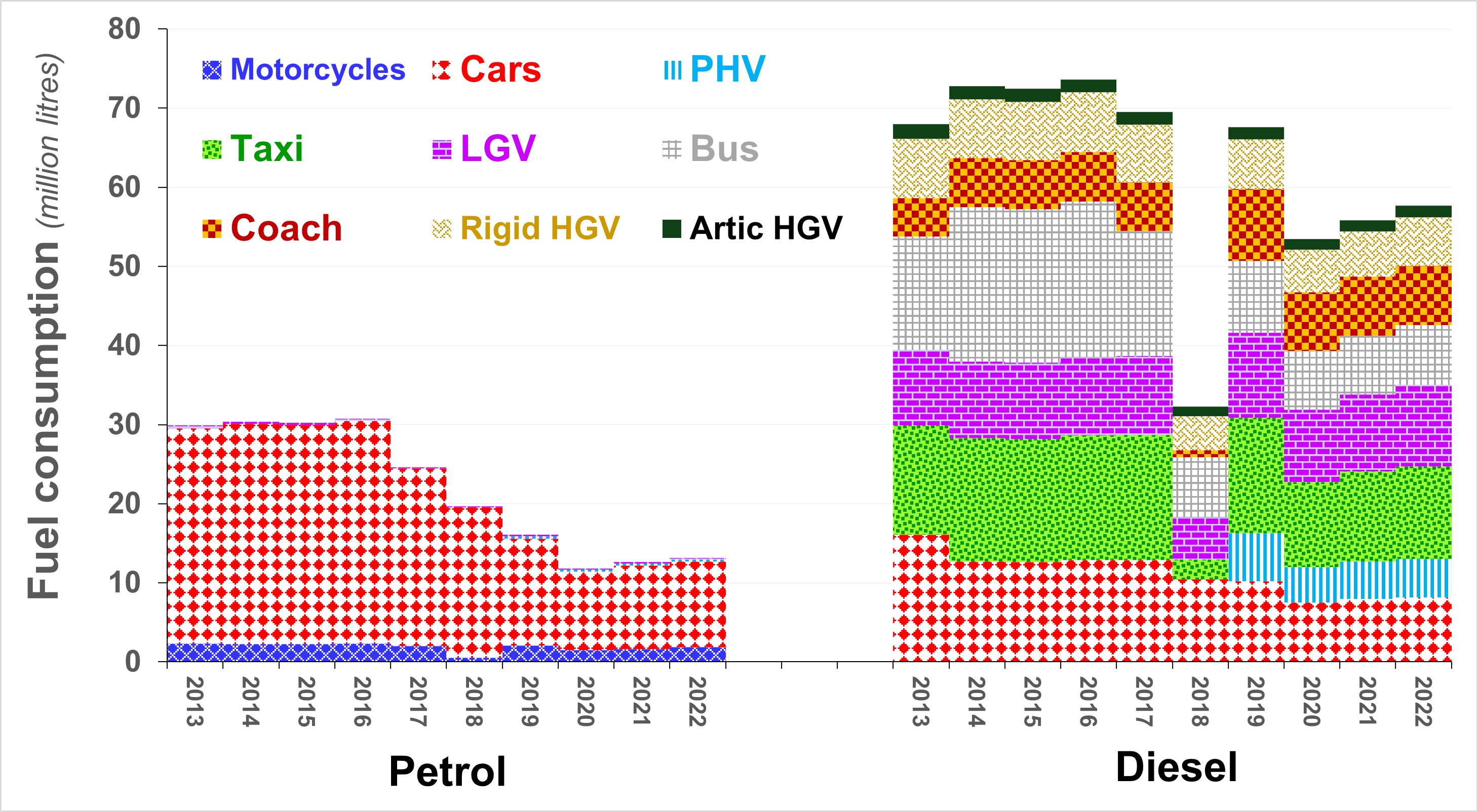

Westminster greenhouse gas emissions from road transport

Westminster City Council stopped sytematically monitoring concentrations of NO2 using diffusion tubes in 2010, the year by which those concentrations should have declined to less than the legal limit (40 micrograms per cubic metre). On the recommendation of both DEFRA and the GLA, the Council has re-started. However, November 2020 is the first month for which measurements have been published, earlier months seeming to have been spent testing diffusion tubes from at least one other supplier. It is standard practice across local authorities in London to publish such data in Air Quality Annual Status Reports for the given calendar year - but only after approval by the GLA and DEFRA. During recent years, approval has taken several months longer than it used to. This tends to reflect lack of government committment, despite ever increasing evidence of the health, social and economic costs of air polution, and despite the climate emergency. The current time lag of 18 months to two years is inexcusable. NO2 concentrations are an important, albeit weak, proxy for greenhouse gas emissions in so far as NO2 in urban areas derives predominaoty from combustion in diesel vehicles and methane ("natural" gas) for heating and cooking. As such, local authorities should publish - on an explicitly provisional basis - their NO2 diffusion tube measurements within two months of the end of the period during which the tubes are exposed.

Click

here for a map of NO2 concentrations (?in 2017) across the

Oxford Street District.

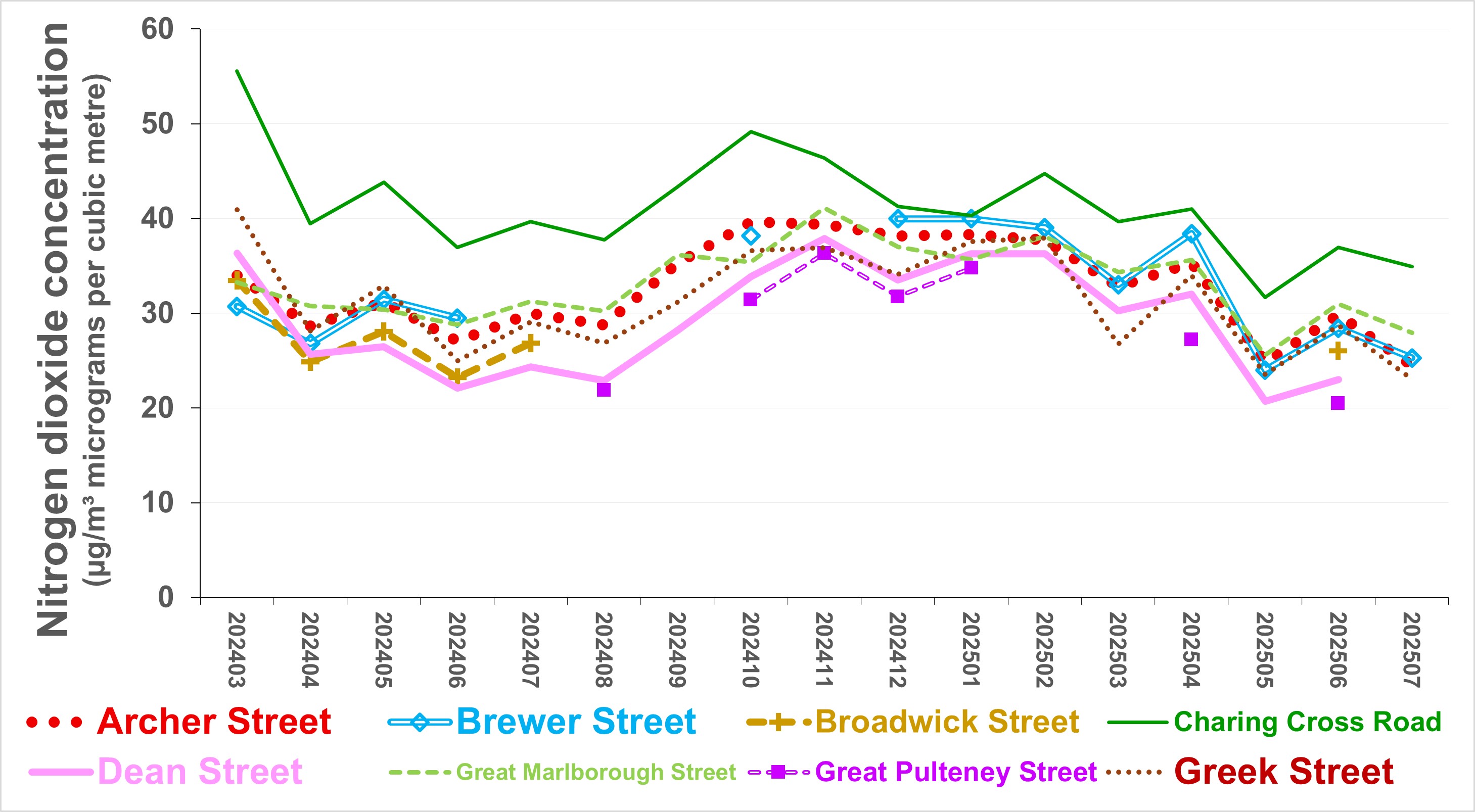

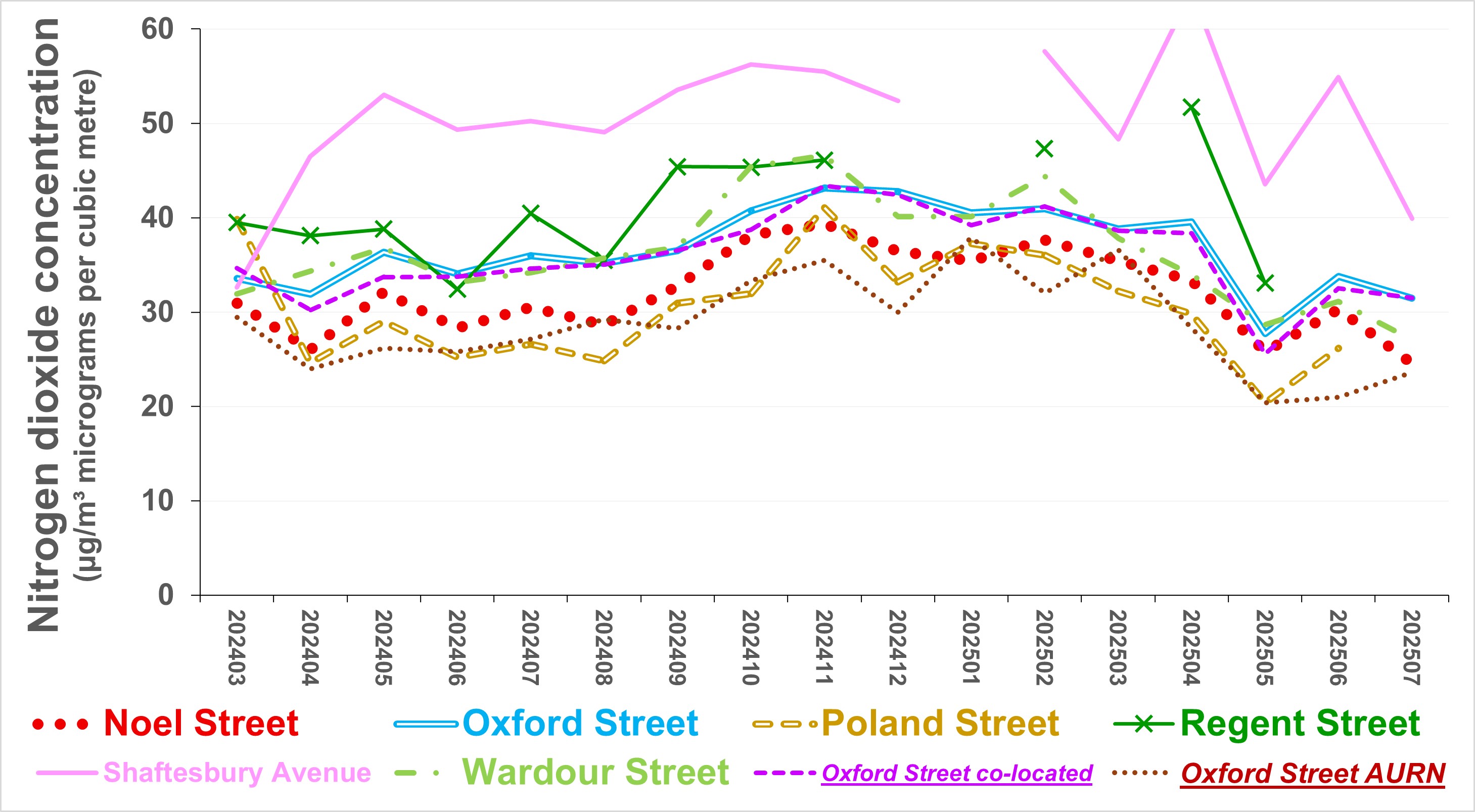

The following two charts illustrate monthly

NO2 concentrations across Soho.

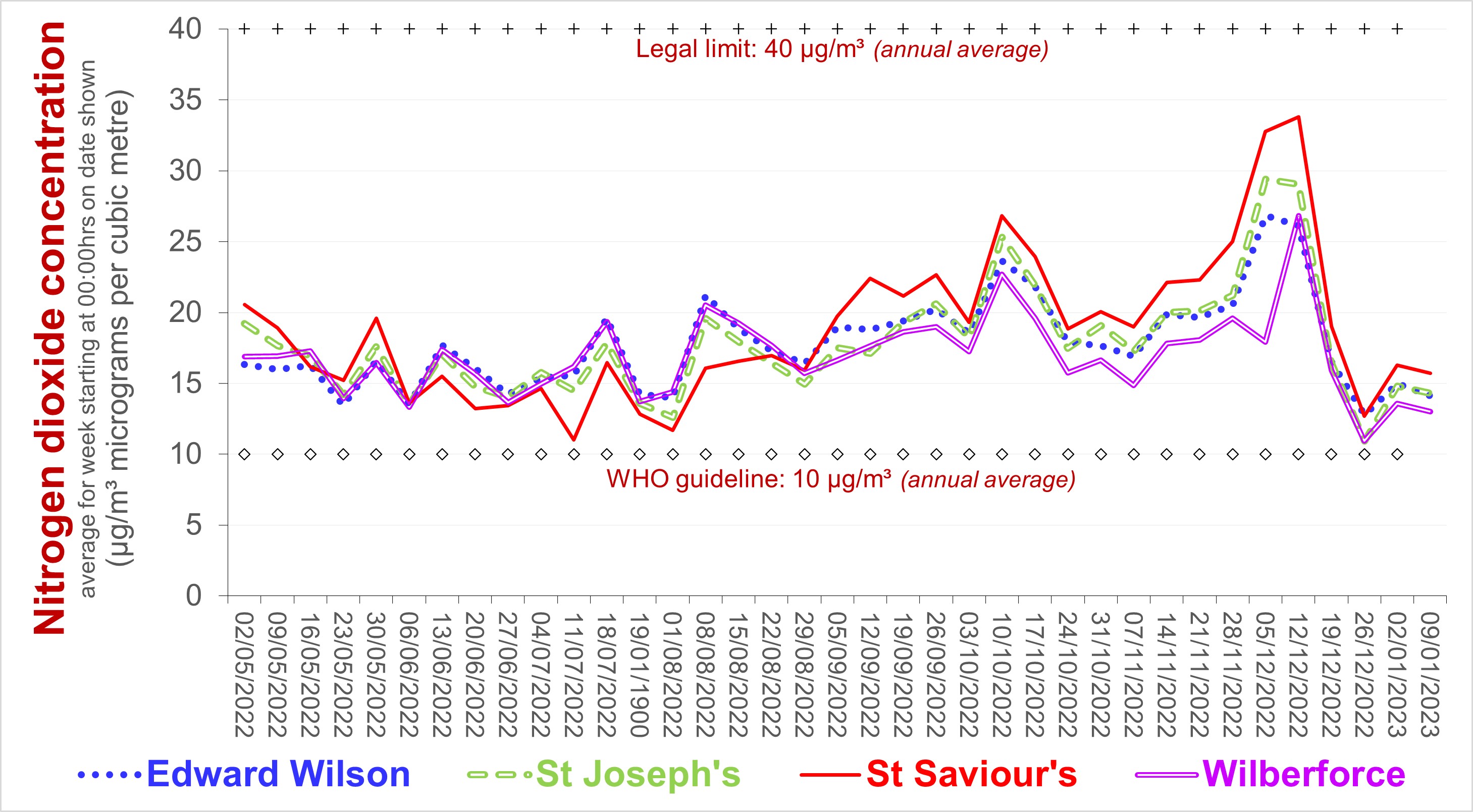

The following chart derives from the public portal for

four schools

in Westminster

Click the chart for PM2.5 and ozone

The cold snap contributed to the December spike, the increase

in NO2 since summer reflects seasonal variation.

Click

here

for charts deriving from and air quality audit of schools

in Westminster

A

summary report

of the audits of air quality which the Council carried out for schools across Wesminster during 2019 and 2020

states

that NO2

concentrations adjacent more than half of those schools exceeded

the legal limit.

That report neither identified which those schools were nor

explained why, despite having authority over most roads adjacent

those schools, NO2 concentrations remain above the legal limit a

decade after they should have been below it. The Council's

subsequent

action includes making recommendations and offering up to £10,000 per school

- but not reducing the pollution at source, for example, from

traffic on roads managed by the Council. One school has been

allocated a budget of roughly £25,000 for air filters - with

no apparent provision for optimising their

location or monitoring their effectiveness. This adds to

the burden of the "innocent victim" and may serve to reduce pressure

to addres the problem.

Deploying diffusion tubes - and publishing measured data every

month - would, at minimal cost, help the

Council, residents and users guage the impact of specific

projects, such as during and after the costly, contentious urban

greening and road works of the the Marylebone Low Emission

Neighbourhood. Concerning the latter, the Council chose not

to do so - monitoring was presumably a condition of the one million

UK£ GLA grant it received for the project.

Court rulings subsequent to cases

brought by ClientEarth oblige government to ensure NO2

concentrations decline to beneath the legal limit in the shortest

possible time. During September 2021, based on 16 years of

evidence and research, the World Health Organisation

revised its advice concerning the maximum annual average

concentration of NO2

and particulate matter PM2.5 - respectively, they are now four and

five times less than the legal limit. Central government has passed the buck to local

councils, obliging them to demonstrate that they are doing all

they can within their power to comply.

It would

obviously be wrong to assume that local councils have sufficient

power to design and implement policies which meet that legal

obligation, especially in London where regional government might

have much greater influence. That said, the Council has now

declared a

Climate Emergency (but its more recent City Plan 2019-2040

almost completely ignores this, thereby almost inviting

litigation). The Westminster Climate Emergency Action Plan seeks

to achieve no more than half of the emissions reduction between

business as usual and what the Tyndal Centre urges by 2040 [page

15].

Research by Imperial College

[see

/ listen from minute 15:10]

indicates that NO2 concentrations are unlikely to meet that

requirement, particularly along those busy streets (and in their

neighbourhood), even when the proposed Ultra Low Emission Zone is

fully implemented across London. A substantial reduction in

vehicle numbers will be essential. Indeed, until the battery

charging network for electric vehicles ceases to rely on

electricity generated by burning fossil fuel or biomass, those

vehicles will tend to accelarate climate change.

|

|

For further information, please contact: info@airqualitymatters.uk |

| Back |